5. Learn how to control taste and flavor.

When invited over to friends for dinner, even before eating, you judge the food by it’s aroma, handing out compliments such as “It really smells nice”! Thankfully, nature is on the cook’s side, because when we prepare food and heat it, volatile aroma compounds are released which trigger very sensitive receptors in our noses. It is generally said that 80% of “taste” is perceived by our nose (what we refer to as aroma), whereas only 20% is perceived by our tongue. How important smell is becomes clear if you catch a cold – suddenly all food tastes the same. Too illustrate the importance of smell, prepare equally sized pieces of apple and pear. Close your eyes, hold your nose and let a friend give you the pieces without telling which is which. Notice how difficult it is to tell them apart. In fact, with a good nose clip you wouldn’t even be able to tell the difference between an apple and an onion! Then, with a piece of either in your mouth, let go of your nose. Within a second you can tell whether it’s apple or pear!

Taste

Our tongue has approximately 10.000 taste buds and they are replaced every 1 to 3 weeks. Their sensitivity increases roughly in the following order: sweet < salt < sour < bitter. In addition to the four basic tastes there is umami, the savory, fifth taste. This taste is produced by monosodium glutamate (MSG), disodium 5′-inosine monophosphate (IMP) and disodium 5′-guanosine monophosphate (GMP). Pure MSG doesn’t taste of much, but can enhance the taste of other foods. There are also some claims of a sixth taste.

A number of taste synergies/enhancements exist. I’ve also included three examples of how flavours can influence taste:

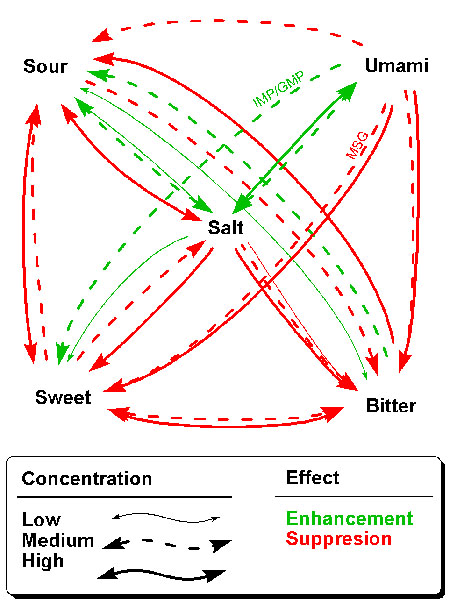

The only general, over-all trend which can be found is that binary tastes enhance each other at low concentrations and suppress each other at higher concentrations (but there are several exceptions!). Do check out “An overview of binary taste–taste interactions” (DOI:10.1016/S0950-3293(02)00110-6) if you’re interested in more details on binary taste interactions. I’ve tried to visualize taste enhancements (green) and suppresions (red) in the following figure using arrows to indicate the direction. For example, salt suppresses sweetnes at high concentrations.

In addition to taste, our tongue also percieves texture, temperature and astringency. An interesting thing about the temperature receptors is that they can be triggered not only by temperature, but also by certain foods. The cold receptor is triggered by mint, spearmint, menthol and camphor. There is even a patented compound, monomenthyl succinate, that triggers the cold receptor, but without the taste of menthol. It’s marketed under the name Physcool by the flavour company Mane.

Substances such as ethanol and capsaicin trigger the trigeminal nerve, causing a burning sensation. Capsaicin also triggers the high temperature receptors of the tongue, hence the term “hot food” which can refer both to spicy food and food which is very warm. For a general article about taste, check out “Taste Perception: Cracking the Code” (DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020064, free download).

Flavour

Our nose has about 5-10 million receptors capable of detecting volatile compounds. There are about 1000 different smell receptors and they allow us to distinguish more than 10.000 different smells – perhaps as many as 100.000! In order for us to smell something, the molecule needs to enter our nose at a concentration sufficient for us to detect. Aroma compounds are typically small, non-polar molecules. The fact that they are small means they will have low boiling points – they are volatile and spread rapidly throughout a room. They are often referred to as essential oils and are very soluble in fat, oil and alcohol. These aroma compounds generally not soluble in water, but there are also water soluble aroma compounds; just think of a well prepared stock – no fat but lots of taste and aroma!

A challenge with aroma molecules is that they should remain intact during storage and not be released until cooking (or even better, until consumption). A example would be to install a Liebieg condenser over your pot. Dylan Stiles has explored this in his column Bench Monkey by placing a bag of ice on top of the lid. He claims that his roommates prefereed the curry which has been cooked under “reflux conditions”. The study was performed in a double blind manner (which I will come back to in part 8 of this series).

Because aroma compounds are volatile, spices should be obtained whole and stored in tight containers away from light. If possible, fresh herbs should be used. The flavour of herbs and spices can be extracted by chopping or grinding to increase the surface area. To speed up grinding in a mortar you can add a pinch of salt or sugar.

Heat can help extract flavour (just think of how we brew tea or coffee), but will also evaporate volatile compounds, so a general advice would be to add spices at the start and herbs towards the end of the cooking time. Some herbs can even be sprinkeled over the food just before serving. In Southeast Asia (and especially India) it is quite common heat spices in a dry pan or in oil. This matures flavours and allows reactions to occur (possibly Maillard reactions). Coarse spices should be added earlier than finely ground spices.

In addition to adding flavour using spices, herbs and other foods, we can also use heat to create new flavours. When sugar is heated, caramel is formed. And if a reducing sugar is heated in the presence of an amino acid, they react and form a host of new flavour compounds in what is known as the Maillard reaction. Caramelisation and the Maillard reaction are known as non-enzymatic browning. Enzymatic browning on the other hand is detrimental to many fruits (such as apples and bananas), but there are a few exceptions. Enzymatic browning is essential in the production of tea (black, green, oolong), coffe, cocoa and vanilla, although this is rarely attempted in kitchen.

Another source of flavour is fermentation. It refers to a process were sugar is converted to alcohol and carbon dioxide by the action of a yeast. In the process a number of flavour compounds are formed as well which is why this is of great interest also from a molecular gastronomy viewpoint. Some examples of fermented products include wine, beer, cider and bread. Fermentation also refers to the process where some bacteria produce lactic acid. Some examples of foods resulting from lactic acid fermentation are yoghurt, kimchi and pickled cucumbers.

Flavour pairing

Cookbooks and recipes throughout the world are the result of billions of experiments. As a result, some very good combinations of herbs and spices have been discovered. Some of these mixtures have even been given names of their own and it is fascinating how easily one can forget that curry for instance is a mixture of spices. Wikipedia has a wonderful overview of herb and spice mixtures from all over the world. I must admit I only new a fraction of these:

Adjika | Advieh | Berbere | Bouquet garni | Buknu | Cajun King | Chaat masala | Chaunk | Chermoula | Chili powder | Curry powder | Djahe | Fines herbes | Five-spice powder | Garam masala | Garlic salt | Harissa | Herbes de Provence | Khmeli suneli | Lawry’s and Adolph’s | Masala | Masuman | Mixed spice | Niter kibbeh | Old Bay Seasoning | Panch phoron | Quatre épices | Ras el hanout | Recado rojo | Shake ‘N’ Bake | Sharena sol | Shichimi | Spice mix | Tajín | Tandoori masala | Tony Chachere’s | Za’atar

A book which I’ve found to be very useful when combining flavours is “Culinary artistry” by Andrew Dornenburg and Karen Page. It is the most comprehensive book about flavour pairing that I’m aware of, and I would say it is indispensible for someone who likes to cook without a cookbook. It has lists of basic flavors contributed by various foods. For example a sweet taste is contributed by foods such as bananas, beets, carrots, coriander, corn, dates, figs, fruits, grapes, onions, poppy seeds, sesame and vanilla (plus sugars and syrups of course). It has lists of “flavor pals”, a term attributed to Jean-Georges Vongerichten. For example, the flavour pals of ginger are allspice, chiles, chives, cinnamon, cloves ,coriander, cumin, curry, fennel, garlic, mace, nutmeg, black pepper and saffron. By far the most extensive part of the book are listings of food matchings. An illustrative example is pork which combines well with (classic/widely used combinations in bold):

apples, apricots, bay leaves, black beans, beer, brandy, cabbage, Calvados, dried sour cherries, clams, Cognac, coriander, cream, cumin, fennel, fruit, garlic, ginger, hoisin sauce, honey, juniper berries, lemon, lime, marsala, molasses, mustard, onions, orange, parsley, black pepper, pineapple, Chinese plum sauce, plums, prunes, quinces, rosemary, sage, sauerkraut, soy sauce, star anise, tarragon, thyme, vinegar, walnuts, whiskey, white wine

Despite the abundance of combinations, I dare say that little is understood about the science behind these flavour pairings. Why do these combinations of herbs and spices go particularily well together? Is it all about getting used to the combinations, so that we learn to like them? What influence does the complexity of the flavour play? These are easy questions that probably have rather complex answers.

Very recently a different approach to flavour pairing has emerged. If two foods share one or more key odorants, chances are that they will go well together. The first step towards finding new pairings would be to identify key odorants. More info on key odorants can be found in the article “Evaluation of the Key Odorants of Foods by Dilution Experiments, Aroma Models and Omission” (DOI: 10.1093/chemse/26.5.533, free download). I’ve initiated the food blogging event “They go really well together” (TGRWT) to explore new flavour pairings and develop new recipes. There are also several blogposts with interesting comments on about flavour pairing.

*

Check out my previous blogpost for an overview of the tips for practical molecular gastronomy. The collection of books (favorite, molecular gastronomy, aroma/taste, reference/technique, food chemistry) and links (webresources, people/chefs/blogs, institutions, articles, audio/video) at khymos.org might also be of interest.

According to Hervé This (and if I remember correctly), the tastes are not limited to the 5 (or 6) ones you mentionned, but there are many more than that: he wrote that liquorice has its own taste, and that a dozen or so of different kinds of bitter tastes have been identified.

Also (again according to This and IIRC), salt also reduces the perceived bitterness.

Btw, why does salt taste so wonderful in the mouth, whereas sea water tastes awful? Is it a matter of concentration?

A dipping accident into Chinese hot mustard at a Polynesian restaurant tonight caused me to ponder part of this posting. You mention the elements in chiles or peppers that create a burning sensation in the mouth, but what exactly is it in mustard that ‘burns’ us? The feeling is the same as with horseradish or wasabi. A burning sensation is felt more in the nasal cavity and in the back of the head instead of a fiery sensation in the mouth.

All of your points above are well-documented and interesting.

By the way, I had never heard of the ‘thinking blogger’ award. Thanks for passing my site on again. I would definitely recommend khymos. I have actually been pushing your posts on a few other chefs around me, and they all find them extremely useful.

Thank you!

I’m having a lot of fun reading your posts, and I can see you put a lot of effort into writing them. I had to learn the hard way when it comes to astringency, I had a bad experience with some unripe sharon fruit at Xmas. Although a horrible experience at the time, since then I’ve gone on to learn more about astringency and other lesser-known taste sensations such as pungency and umami (I’m also now fascinated by the Maillard effect and am trying to pass on the knowledge I’ve gained to others). This is a very interesting blog you’ve got here, and being so very different it’s also a nice change from the majority of blogs I read. Keep up the great postings!

Matthieu: Yes, it’s correct that different bitter tasting substances trigger different receptor cells. This discusses this in his book on p. 100-102. I was not aware that liquorice is a taste category of it’s own. Do you remember where you read about it?

Chadzilla: It’s the same class of chemicals that are responsible for the pungency in mustards, wasabi and horseradish, namely isothiocyanates, especially allyl isothiocyanate (wikipedia article with molecular structure after the jump). This compound is not present to start with, but once the cells are disrupted, enzymes liberate it.

And thanks for all the praise! Good to know the blog is actually useful to some people!

I searched through a couple of databases and did not find anything about a liquorice (taste-)receptor. The increase in blood preassure and reduction of body weight(?) due to liquorice is well documented, though no mention of the stomach protection properties liquorice was prescribed for en gros over 100 years ago.

So we are left with the 5 taste categories and the direct irritation of the mucous membrane (aka mouth) by e.g. chillis.

P.S.: The book by Hervé This quoted from above is: ‘Molecular Gastronomy’ 2002 (french edition), 2006 english translation.

You give one example of how the ‘sixth taste’ influence one of the other five [black pepper reducing sweet]. I do like the way you visualize taste enhancement & suppression but I miss in the figure the sixth taste [certainly after the mustard-mint adventure].

[…] Practical molecular gastronomy: Learn how to control taste and flavor […]

First, about synergies/enhancements, Breslin et al. from Monell Chemical Sense Center explain how sodium salt is responsable for bitterness inhibition. Intersting if you want to apply this knowledge on gastronomy.

Second, I read some papers about sixth taste and “fatty” has many chances to be the sixth…

Anybody have a clue?

is there any taste bud for fats